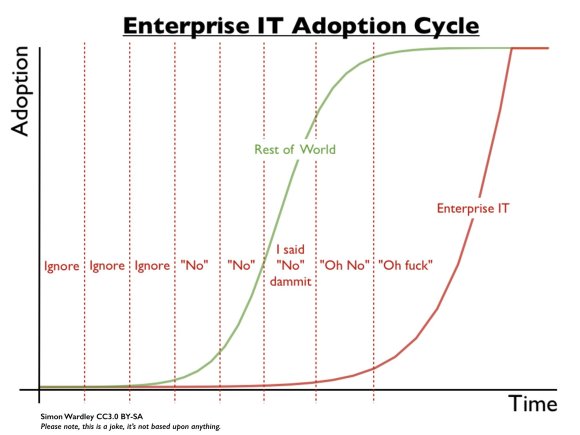

Simon Wardley, the creator of the always useful “Wardley Maps” has a quip he shared a few years ago about the speed that the IT departments of large enterprises react to technological change.

While funny, the humor is pretty close to how we all see enterprise computing. Many would argue that government is the same. It is a common litany that government is slow and unresponsive. We often hear comments about how government workers are lazy, or that governments should be run like a business. In this article, I will use a pace layer model to push back against this argument, and then offer a more nuanced point of view.

Pace Layers

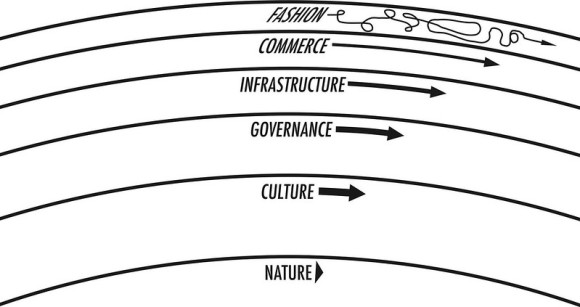

In the late 1990s, Stewart Brand postulated that what we now call complex adaptive systems can stratify into temporal layers that move at different speeds. The higher layers in the model move at a faster pace than those below. The layers coexist, but there is friction at the interfaces between each layer. The friction causes conflict, change, innovation and development.

Great fleas have little fleas upon their backs to bite ’em, And little fleas have lesser fleas, and so ad infinitum. And the great fleas themselves, in turn, have greater fleas to go on; While these again have greater still, and greater still, and so on. [Augustus De Morgan. A Budget of Paradoxes]

The image below is the reference layering model from Brand’s work. I imagine that with some thought, you can imagine smaller systems and their pace layers. The smaller systems are a part of the model below, giving us layers within layers.

As we can see, commerce moves faster than government (which normally resides in the governance layer). If we think about the dynamics of markets, then this assertion makes sense. Companies learn how to exploit a new resource (or an old resource in a new way), and markets quickly form. Governments neither understand nor care about the new market until societal risks need to be mitigated. At that point, laws will be passed and regulations enacted. This constrains the market and, if done correctly, reduces the impact of the risk.

Shearing Strains

Looking around at the world as it is today, we can see some shear points between the layers. I am going to mention three here and then get back to the point.

Culture Wars and the Impact on Higher Layers

If we look at the Culture layer and think about sub-layers within it, we can imagine fast-moving popular culture, the slower moving progressive layers below it, and the even slower conservative and religion layers under that. As popular culture became purified by the commercial pressures of broadcast and social media, the pace of change in popular culture increased. We can safely say that the faster progressive layers cause friction with the slower conservative layers below (think about gay marriage.) The shearing effects can partially be seen as political polarization. This polarization spills into the governance layer above with effects like gridlock in the US Senate, the Trump Presidency, Brexit.

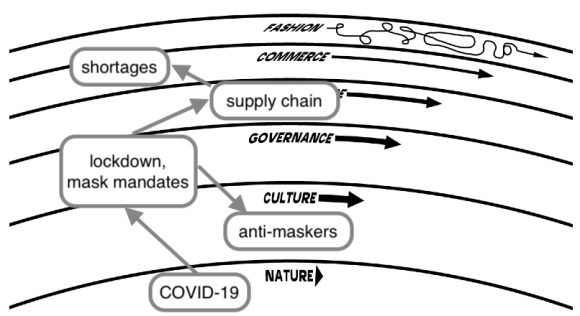

COVID-19

When the lower layers move, it is often discontinuous and causes massive changes in the layers above.

The emergence of the new coronavirus caused governments to respond quickly. They enacted some drastic measures, like social distancing, restrictions on commerce, mask mandates. These measures caused a cultural backlash with, for example, the rise of anti-maskers. They also caused supply chain stoppages which in turn created shortages of goods.

These are not the only effects. Think about the vaccine programs and more.

Web 2.0 and Cloud Computing

In the early 2000s, the build-out of the Web 2.0 infrastructure began, enabling a richer e-commerce experience. The maturing of cloud computing formed a catalyst for ubiquitous internet commerce, social media, and the ascendence of massive internet empires.

Governments have not regulated much of internet commerce yet. They have stuck to what they understand, like regulating the wires. It is becoming clear that government needs to decide how to regulate commerce, social media, and rethink intellectual property. When this happens, it will have ripple effects through both the infrastructure and commerce layers.

The Speed of Government

As we have explored, government exists at a lower, slower temporal layer than fashion, commerce, and infrastructure. This gives it the ability to remember what the higher layers learn, and the power to regulate the higher layers.

Commercial services last as long as they are profitable. In the accelerating world of modern capitalism, the length of time you can be profitable is shorter by the decade. Customers do not rely on a commercial offering to be available forever.

On the other hand, government programs must be relied on for generations. Whether it be a levee or Social Security, we expect them to be there and functioning for our lifetime. This long-term dynamic is at odds with the quarterly and annual return focus of commerce. This is why a government should not be run like a business. You cannot move fast ad break things with Medicaid. Lives are at stake!

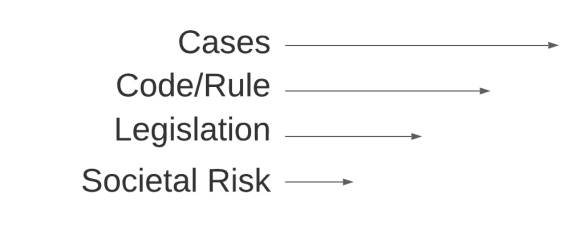

A Pace Layer Model of Government

Let’s keep looking because there is more to see.

The workings of government can also be separated into pace layers. This is my interpretation of how they are.

At the bottom are societal risks, the thing that a government responds to. The response is legislation, which can be in statute for generations. From the legislation, federal code or state administrative rule is created. For active programs, federal code/administrative rules can change on an annual basis. Cases are individual interactions with private entities who are availing themselves of the program. This could be an economic assistance application, an alleged rights violation, an inspection of a regulated business process, or any of the myriad things government does. Programs may handle hundreds to hundreds of thousands of cases per year. A case is the application of administrative rules to an individual situation and each situation is different. This need to be flexible causes friction with federal code/administrative rules. Administrative rules change in response to changing legislation, changing interpretations of legislation, and changes of practice when handling cases. The interpretation of legislation and hence the spirit of the administrative rules are often driven by the politics of the elected and politically appointed officials. Ultimately, the admin rule must adhere to legislation.

Could it be that when folks talk about running government like a business, they are thinking about the fast-moving cases layer? It is certainly true that the more cases completed, the more the societal risk is mitigated. Working to a fixed budget means that the more efficient you are, the more cases you complete. Therefore, some process improvement techniques could make a difference to the number of cases completed. That does not necessarily mean the methods of tracking revenue, return on investment, and strategic planning that the private sector uses are either appropriate or effective. Why? Because the administrative rule and budgeting processes will subvert them.

So, hopefully, I have established that government is not like business and does not operate like one. It does not operate at the speed of commerce and probably never will. However, there are things that government can and should do to improve the effectiveness of its programs.

You must be logged in to post a comment.